Candidates, Why go through a recruitment agency ?

1/ Your chances of finding a job are multiplied If you respond to a job offer published by a recruitment agency, your application will not…

Architecture has always been full of meanings and symbols, whether deliberately encoded in its different structural elements or expressed by more abstract and general spatial organisation principles. Architecture not only organises different aspects of our daily life but it also conveys meanings, feelings and emotions. Architecture can be hostile or friendly; it can convey a sense of belonging or be alienating. The space shaped by architecture directs our movements and puts us in deliberately planned behavioural ‘scenarios’. In this regard a truly good architect might be considered the one who not only thinks about the comfort of our body but also about the comfort of our psyche. In the building of the Tribunal of Paris the celebrity architect Renzo Piano has shown himself as a true Architect with the capital letter. An architect who not only simply constructs a shelter for humans and provides them with a space to exercise their daily life, but an architect who is concerned with the emotional state of those who will be using this building, and thinks about constructing their state of mind as well.

A court house, like the White House, is one of the most important symbols of any state. France, as one of the most egalitarian and democratic countries in the world has the “liberty, equality and fraternity” as its main slogan. So, how should such an iconic governmental building, as a court house manifest this belief?

For centuries the classicism enjoyed the autocracy in the western architecture. With its sumptuous, richly decorated facades and interiors, by means of its monumental aspect and scale this style has been always associated with power and wealth or with the elite in other words. This is definitely not the style with which common people, that are the majority of any society, can associate themselves.

That is why Renzo Piano has opted for what can be considered a quite a daring decision: to strip off the building of his court house of its traditional classical and monumental aspect, and make it something utterly neutral in its stylistic message, contemporary and friendly by its aspect. Surely the professional community of lawyers, who are obliged to maintain traditionally set canons, might not perceive well these innovations. In fact there have indeed been some complaints about moving out from the previous centrally located classical architecture building into this suburban glass tower. But sometimes positive and constructive innovations start from the innovation of the environment and then transfer into the mindset of people.

Piano has been also respectful for the urbanism of the area and Paris skyline in general. He tried to create an architectural form and volume that would not be overwhelming and oppressive by its massiveness in the area. Hence he chose the recessing tiered structure in order to create a high-rise

that would not be perceived as a dominating tower. The overall composition consists of three superimposed blocks that are separated by thin line of a gap, thus breaking the monolith and massive aspect of a tower. The choice of transparent glass to face the building makes it ethereal and light. In fact the scale of the building is never really perceived, as from close the upper tiers are cut in the perspective. The whole body of the building can be perceived only from very far. Thanks to its configuration of a stretched rectangle the building is perceived as a thin tower while looking from the North and the south, and as a composition of gradually diminishing tiers from the west and the east. In both cases the building, despite its impressive height doesn’t look to be in dimensional dissonance with its surrounding, although it is indeed the tallest building in the whole area.

When approaching the building one sees a modest, neutral building of transparent glass that radiates lightness and light. The main entrance placed on the south-western facade has no accent except a simple rain cover. Nothing hints of any special or dramatic passage into a place where destinies of people can be changed. Indeed, Piano himself has noted that people who visit this building are already not in a perfect emotional state and that there is no need to accentuate their entrance into a place which embodies power. Visitors first enter through a small turning door into a

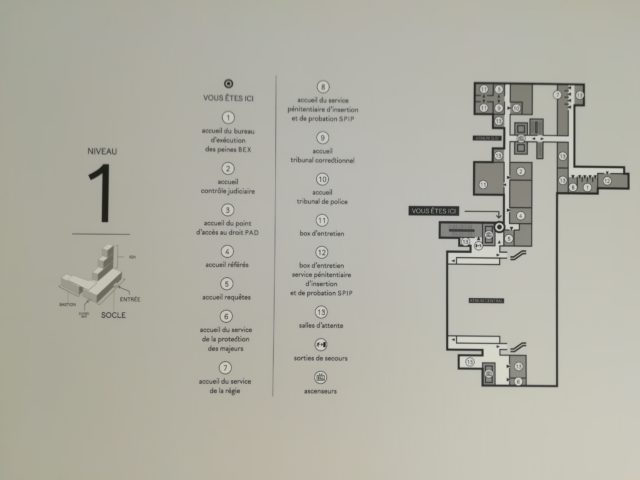

rather simple hall where they pass the security check. The walls of the hall are marked with inscriptions from the legal codex stating about human rights and freedoms. All in all everything is done by architectural means to not only not to suppress human dignity but also to encourage and welcome visitors into a house of justice, and to accentuate that justice is done for people!

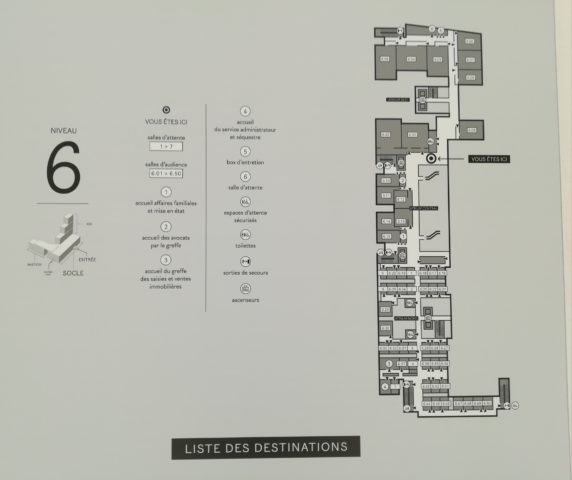

After the security check we find ourselves in another relatively large hall. The corridor leads us to the left into the atrium-“Le sale de ne pas perdues”. After this passage we find ourselves in a large white, transparent atrium totally open to the city and full of light. The interior is overly white, lit and

transparent suggesting with its spatial and material transparency the transparency of justice. The reception kiosk is located in the middle of the hall and rows of whitewash benches offer places of rest to the visitors. Escalators on either sides of the hall lead until the sixth floor and elevators take flows of people down. There are several other elevators located in the either ends of the corridor, each of which creates another smaller atrium. The access of visitors to stories above the sixth floor is forbidden, which are served by other elevators at the other end of the corridor.

By the spatial and volumetric configuration of the building and by means of interior space organisation and used materials Renzo Piano has tried to create as neutral yet pleasant, positive atmosphere for the visitors as possible. Architecture, as a very eloquent art, conveys these ideas of peace, freedom, transparency and equality.

By Yeva Ess-Sargsyan